Companies would be wise to ensure that all suppliers have gone through due diligence before signing a contract.

Recently, a Toronto-based law firm filed a class action lawsuit of $2 billion in damages against a major retailer in Canada in relation to the 2013 Rana Plaza Bangladesh garment factory collapse, in which over 1,000 people lost their lives and over 2,500 were gravely injured.

Is the legal system the best way to create change?

The lawsuit alleged that the retailers had prior knowledge about the “extremely poor record” of workplace safety and industrial building standards in Bangladesh. The allegations also claim that the retailer was aware of the “significant and specific risk” to workers who manufactured the brand’s garments and whom their subcontractors in Bangladesh employed.

Who’s responsible for looking out for human rights and environmental harm?

In France, a proposed law seeks to make parent companies liable for human rights’ violations as well as health and environmental damages committed abroad by subsidiaries and suppliers. This could represent a civil and criminal liability if breaching the duty of care of at least taking preventive measures to prevent the damage to occur.

Lawsuits as well as new potential laws, such as the French proposal, puts a new form of spotlight on the complex issue of supply chain governance, human rights due diligence and now the growing question of legal risks and liabilities.

Human rights and environmental problems in the supply chain have been in and out of the spotlight since the mid-1990s when public campaigns began to be directed at big brands for selling products made under poor conditions in supply chains, mainly in developing countries.

This changed the public opinion about the responsibility of global firms towards their supply chains, including the opinion of shareholders who wanted to hold companies to “higher standards” as compared to the limited existing laws and regulations in the countries of operation. At that time, media stories and public judgement was the main concern for the C-suite and the Boards of Directors. Bad publicity affected the reputation and the sales of the company’s products.

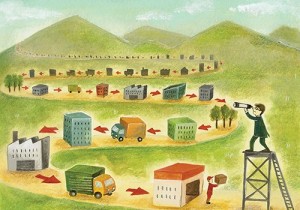

As a result of the growing media spotlight and greater interest in what is going on in the supply chain, most large companies today have a more or less sophisticated responsible supply chain program. The key components in such a responsible supply chain management program are:

1. A code of conduct describing what is expected from the supplier.

2. An investigation process (via questionnaires and/or on-site visits/audits) of the risks of suppliers’ non-compliance with the code of conduct.

3. Improvement programs. Companies who have found child-labor or other “non-acceptable” factors in their supply-chain have been told by stakeholders that the right thing is to continue the relationship with the supplier and work to improve the situation. And only in cases where the supplier is not willing to improve, all business with the supplier should be stopped.

4. Training sessions and working with other businesses to improve the situation in order to have a greater positive impact.

Although progress has been made, working conditions in supply chains around the world and across industries are still not on par with most of the western world. Conducting supplier audits, human rights due diligence and continuous improvements are of critical importance for the workers, the environment and the reputation of the company.

Putting their heads in the sand cannot be an option

Facing this situation, companies are caught between a hard place and a rock. On the one hand, conducting supplier visits and human rights due diligence might lead to the discovery of facts that might increase the company’s exposure to liability claims. On the other hand, not taking action can result in reputational risks, and hit sales and stocks hard and is also out-of-line with the values and policies of many companies.

In light of companies facing lawsuits for having knowledge about the conditions in their supply chain, the following questions arise: Are companies exposing themselves to more potential public judgement or lawsuit claims by keeping an eye on their social and environmental impact in their supply chains? Does conducting supplier visits or human rights due diligence increase a company’s risk of liability and allegations? How much can or should the companies get involved, what actions must they take, and how can they improve the situation without putting themselves at risk for lawsuits?

The new French law proposal requires companies to establish a “duty of care roadmap” that prevents human rights violations as well as environmental damages and at least take preventive measures to prevent the damage to occur.

In a report to the U.N. Human Rights Council, Professor John G. Ruggie articulated his well-known “Protect, Respect, and Remedy” Framework. The framework outlines that the business responsibility to respect human rights requires companies to conduct human rights due diligence.

What kind of suppliers do we as a company want? Are we willing to pay more? And therefore, can we ask our customers to pay more?

This means adopting a human rights policy, conducting human rights due diligence, integrating the policy into the company’s operations and culture, and tracking and monitoring performance. Human rights due diligence is prudent as ever because it allows companies to identify potential human rights risks before they occur, which should therefore reduce companies exposure to litigation and help companies defend human rights claims that might be filed. However, what to do if the non-compliance has happened?

The C-suite and the Board of Directors must get involved

Companies can and should not shy away from knowing about the conditions in their supply chain — on the contrary, they should put even more focus on this aspect — and demand that their suppliers and sub-suppliers do the same. It is also vital for the C-suite and the Board of Directors to get involved by:

1. Discussing the criteria and the code of the conduct for their own facilities as well as those of suppliers. It is essential to ask questions such as: What kind of suppliers do we as a company want? Are we willing to pay more? And therefore, can we ask our customers to pay more?

2. Discussing the underlying reasons for why suppliers don’t comply with environmental and social standards — is it due to the lack of knowledge and training? Or is it because the company is forcing the suppliers to cut corners due to short delivery-notices, setting unreasonably low prices for the goods they supply, or simply that the suppliers do not care? (If it is the latter, then the relationship should be discontinued).

3. Discussing the key actions and the reports that the board would like to receive in order to perform the needed oversight.

4. Discussing what actions to take internally and towards the supplier when different forms of non-compliance issues are identified.

Companies will benefit from ensuring that all potential suppliers have gone through a due-diligence process before a contract is signed. In this way the company can engage with suppliers that meet the expectations from the management team and the Board of Directors as well as future legislation.

By holding themselves and their suppliers to a higher standard, companies will reduce the risk of having to receive negative comments about the conditions of the suppliers in the media or a civil or criminal liability case in the courtroom.

Supply chain governance issues, human rights due diligence and all sustainability matters require the board to stay informed and take action. As the saying goes, “What gets measured gets managed.”

This article was originally published on Greenbiz

_______________________

Helle Bank Jorgensen has worked with leading companies and organizations within sustainability and climate change for 25 years. She is the CEO of B. Accountability a consultancy helping companies to be successful by being accountable and a global board facilitator for the UN Global Compact Board Programme and the Head of the UN Global Compact in Canada.

Marvelous , Indeed.

is there any law coming about preventing delays from the administrations, state controlled cies and local communities ?

Bruno